27/09/2024

By Prof. Georgios Panos, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece)

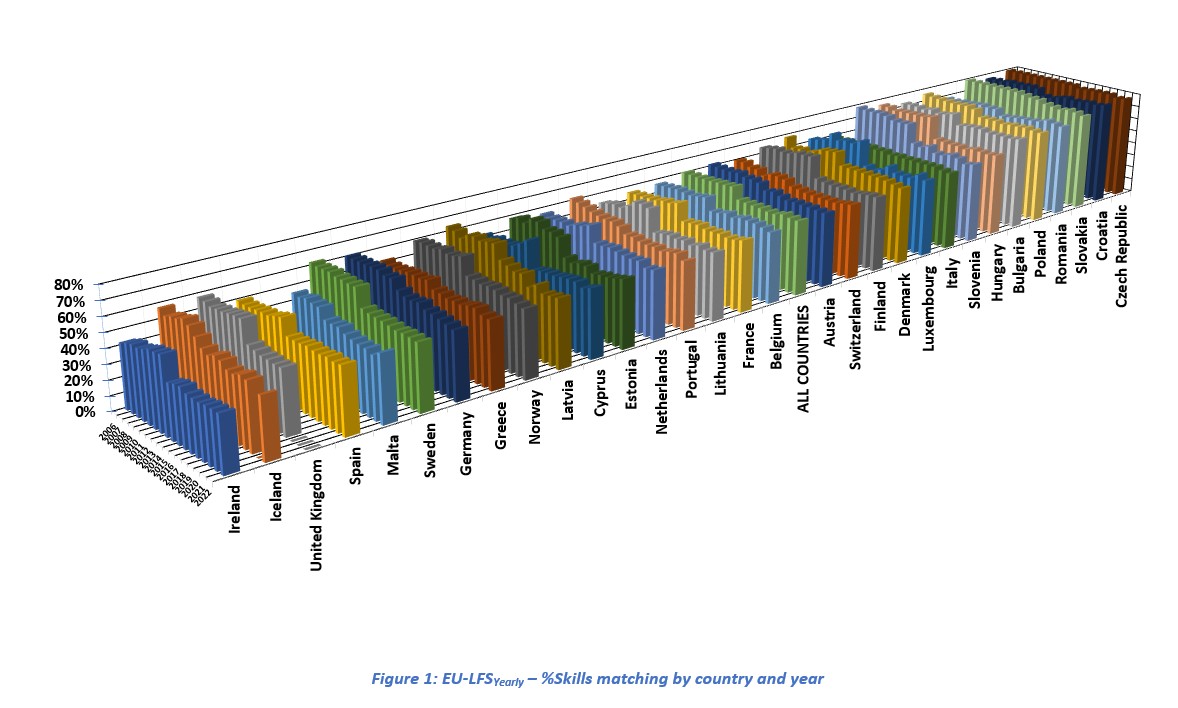

The first quarter of 2014 brought about the largest increase in skills mismatching across European labour markets. Using data from some 46 million European employees between 2006 and 2022 from the yearly EU Labour Force Survey[1], figure 1 documents this massive decline in skills matching[2] in European labour markets (Panos, et al. 2024).

How big was the decline?

At the peak of the Eurozone debt crisis between 2013 and 2014, all countries experienced large declines in skills matching ranging between -3.2% (Czech Republic) and -29.5% (Ireland). The absolute magnitude of the increase in skills mismatching was between 2.7 and 15.5 percentage points. The only exception was Iceland, which started experiencing large rises in mismatching gradually between 2010 and 2014, in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. An inspection of the quarterly data of the EU-LFS confirms that it was the first quarter of 2014 which brought about the biggest drops in skills matching in labour markets across Europe.

Why did it occur?

The notable increase in skills mismatching in 2014, as opposed to previous years, can be understood in the context of several economic, political, and structural factors that either fully materialized or became more evident around that specific year. While the groundwork for these mismatches was laid earlier, particularly in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and Eurozone debt crisis, the specific dynamics converged in 2014 for the following reasons:

Is there any recovery?

Around 2014, the European Union and national governments began shifting their focus more explicitly toward addressing the skills gap. The EU launched initiatives like the Youth Guarantee and the European Skills Agenda to help reduce youth unemployment and improve skills matching. These initiatives recognized the growing gap between the skills taught in education systems and those demanded by the labour market, and they aimed to provide training and reskilling opportunities to workers across Europe. By 2014, the EU’s focus on transitioning to a green and digital economy began to take shape.

It is clear from figure 1 that European labour markets have not yet recovered from the mismatching shock that occurred in 2014. The recovery has been modest and can be seen mostly in the new member states of Easter Europe, which were affected the least in 2014. This pattern can not be seen in other datasets that only provide snapshots at different points in time post-2014 from smaller samples.

Conclusion:

2014 was a pivotal year for skills mismatching in Europe because it marked the intersection of several factors that had been building up since the global financial and Eurozone debt crises. Economic recovery started to gain traction in 2014, but it revealed deeper structural labour market issues that had been masked by the crisis. Technological advancements, the effects of prolonged youth unemployment, labour market reforms, and migration trends all became more pronounced, highlighting the mismatch between the skills that workers had and the skills that employers needed. Thus, while many of these trends began earlier, they culminated in a significant increase in skills mismatching in 2014 specifically, from which the European labour markets have yet to recover. The realization that Europe needed to upskill and reskill its workforce to meet the demands of the green transition and digitalization led to new policy initiatives. This acknowledgment of the mismatch in digital and green skills also contributed to the focus on the issue from 2014 onwards.

[1] The EU-LFS covers several millions of individuals from 27 EU countries, and 4 non-EU countries, namely Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

[2] The notion of skills matching used is the vertical definition, i.e., the highest educational qualification being similar to that of workers in a given country, year, and occupation category (3-digit ISCO code).

Georgios Panos (44 years old) is a Professor of Finance at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and an Affiliate Professor of Finance at the Adam Smith Business School at the University of Glasgow, where he worked for the past 10 years. He has held previous positions at the Universities of Stirling and Essex. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Aberdeen (2010), a MSc Economics from the University of Warwick (2004), and a Bachelor’s degree in Economics with honors from the University of Ioannina (2002). He worked as a consultant at the World Bank for a total of seven years, focusing on financial and private sector development, entrepreneurship, and poverty reduction. He has collaborated on financial literacy enhancement programs with the World Bank for developing countries. His research activities in financial management, financial education, and skills matching and development have led to the attainment of major research programs funded by the European Union, such as the PROFIT program (2016-2019: €1.6 million) and the TRAILS program (2024-2027: €3 million). He is an Associate Editor of the European Journal of Finance, as well as a member of the editorial boards of Small Business Economics: An Entrepreneurship Journal and Journal of General Management. In April 2020, he was recognized as one of the best 40 MBA professors under the age of 40 globally by the American organization Poets&Quants, which ranks global postgraduate business administration programs. His published and ongoing unpublished studies on personal finance, financial management, financial technology, financial literacy, skills matching and development, as well as financial and social exclusion, are critically impacting these top-priority policy, education, and practice agendas.