08/05/2024

by Dr Paul Redmond and Luke Brosnan, The Economic And Social Research Institute (Ireland)

What is Skills Mismatch?

Skills mismatch is a broad term that incorporates a variety of different concepts. The most commonly studied measure is vertical mismatch, which occurs when an employee’s skills or education level are either too high or too low compared to what is required to do their job. For example, a person with a masters degree working in a job that requires only an undergraduate degree would be “overeducated”. On the other hand, a person with an undergraduate degree working in a job that requires a masters degree would be “undereducated”. Other forms of mismatch include horizontal mismatch and skill shortages. Horizontal mismatch occurs when an employee’s field of education does not relate to the occupation they work in. Skill shortages occur when employers cannot find suitably qualified workers to fill vacancies.

Why is Skills Mismatch Important?

Skills mismatch can have important consequences for both employers and employees. Firstly, for employees, a large body of research has found that overeducation is associated with a wage penalty. An overeducated employee may be paid 10-15 percent less than an employee in a matched occupation with the same level of education (McGuinness et al., 2018). By stunting skills acquisition, mismatch can leave a lasting scar on individuals’ earnings, even after they switch to a matched occupation (Guvenen et al., 2020). As well as wages, being overqualified can also lead to lower job satisfaction for employees (Cabral Vieira, 2005).

Like vertical mismatch, horizontal mismatch has also been found to be associated with a wage penalty for employees. This wage penalty is particularly large for employees who are horizontally mismatched for involuntary reasons, such as no other job being available (Bender and Roche, 2018). Other work, however, has found that horizontal mismatch only leads to a wage penalty when the worker is also vertically mismatched (Montt, 2015). In addition, horizontal mismatch is associated with lower job satisfaction and a higher level of employee turnover (Bender and Heywood, 2009; Béduwé and Giret, 2011).

Vertical mismatch also has important implications for a firm’s performance. Firms that employ undereducated workers have been found to be both less productive and less profitable. This has been highlighted as an “alarming result” that requires more initiatives across European countries to tackle undereducation and to ensure workers’ skills and knowledge remain up-to-date (Kampelmann et al., 2020). On the other hand, hiring more overeducated workers is associated with both higher profitability and productivity, especially among high-tech firms (Mahy et al., 2015). Skills shortages, whereby firms experience difficulties recruiting employees with the appropriate skills, have been found to lead to negative consequences across a range of measures. Firstly, skill shortages have negative consequences for firm productivity (Bennett and McGuinness, 2009). However, the consequences of skill shortages have wider implications, with potential negative impacts on GDP, employment and earnings (Frogner, 2002). One estimate indicates that a 10 percent increase in the number of firms experiencing skills shortages lowers investment by 10 percent and research and development (R&D) by 4 percent.

The Role for Policy

Given the potentially harmful impacts of skills mismatch, it is perhaps unsurprising that this is a policy area that receives a great deal of attention and funding at both a national and international level. In May 2023, the European Year of Skills ran for the past 12 months. This is a major EU initiative with the broad aim of reducing skills shortages and helping individuals to upskill and retrain so that their skills and education match current requirements in the labour market.

It is envisaged the European Year of Skills will provide a fresh impetus for achieving several skills-based targets that form a core part of EU policy. For example, the EU 2030 social targets aim to have at least 60 percent of adults in training every year. The 2030 Digital Compass sets targets of at least 80 percent of adults with basic digital skills, along with 20 million employed ICT specialists in the EU. Current metrics suggest that there is still a long way to go to address issues related to skills mismatch in Europe. It is estimated that three quarters of companies in the EU find it difficult to recruit employees with the required skills, while just 37 percent of adults undertake training regularly.[1]

Trends in Vertical Mismatch in the EU

Using data from the European Skills and Jobs Survey (ESJS), we examine the prevalence of vertical mismatch (over- and under-education) in the EU over time. The ESJS is administered by the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop),and is an EU-wide survey aimed at collecting information on skill requirements and skills mismatch in Europe.[1]

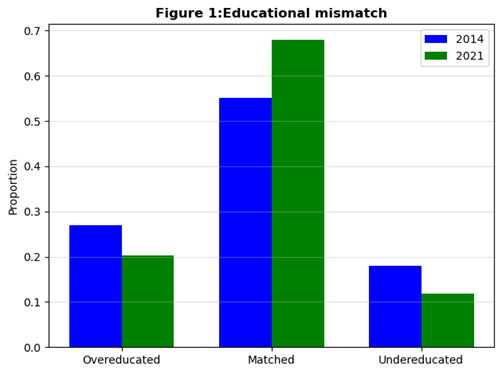

Figure 1 below shows the average incidence of under- and over-education in the EU over two time periods – 2014 and 2021. We see that both over- and under-education decreased over this time period. The average rate of overeducation of participants in the survey went from 26 percent in 2014 to 20 percent in 2021, while undereducation went from 18 percent to 12 percent. There was a corresponding increase in the incidence of workers in matched occupations, going from 55 percent to 68 percent. While this is an aggregate picture for the EU overall, it hides significant country level variation. For example, countries including Croatia, Portugal, Czechia and France experienced particularly large decreases in overeducation rates, while in other countries, such as Germany, the rate of overeducation remained flat. For undereducation, countries including France, Poland, Ireland and Italy saw large falls in the percentage of undereducated workers. Understanding what is driving changes in skills mismatch over time is one of the key areas of study for the TRAILS project. Forthcoming research will provide important insights and policy relevant evidence for understanding changes in mismatch over time in Europe. The country level insights offered by the TRAILS research will be particularly valuable for improving our understanding of the different experiences of individual EU countries.

What Leads to Skills Mismatch?

While understanding the changes over time in vertical mismatch in Europe is an ongoing area of active research within the TRAILS project, we can look to the existing literature for information on the potential drivers of skills mismatch, in particular overeducation. Overeducation has been found to be more prevalent among social sciences graduates, while a vocational qualification is associated with improved matching (Oritz and Kucel, 2008; Marvomaras et al., 2010). Overeducation also tends to be more prevalent in areas where commuting is difficult, as this may pose a barrier to workers finding a matched job (McGowan and Andrews, 2015).

At a broader level, overeducation represents an imbalance between the supply and demand for highly qualified workers. While national governments continually pursue greater educational attainment, if the number of available high-skilled jobs does not keep pace then this will lead to increases in overeducation (McGuinness et al., 2018). Overeducation is also likely affected by changes in economic conditions, as during recessions the demand for labour, and how workers are used within firms, is likely to change.

As the TRAILS project will analyse changes that occurred between 2014 and 2021, a potentially important factor is the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to fundamental changes in labour markets across the world, which likely affected levels of skills mismatch. There was significant movement of workers, as people moved out of sectors that were negatively impacted by the pandemic into sectors that were not. As noted by ONS (2021), the impact of this, in terms of increasing or decreasing mismatch is not clear, as some displaced workers will find a matched job while others will not. In this article, we have highlighted some of the key policy areas relating to skills mismatch. In the coming months and year, the TRAILS project will provide important evidence to improve our understanding of skills mismatch in the EU.

Dr Paul Redmond is a Senior Research Officer in the Economic Analysis Division. His research interests include labour economics, applied econometrics and political economy. Paul has published in academic journals such as the Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Oxford Economic Papers, Public Choice, Journal of Economic Surveys and the European Journal of Political Economy. Paul obtained his PhD in Economics from Maynooth University in 2014.

Prior to joining the ESRI, Paul was a lecturer in economics at DIT Aungier Street and a research associate for the Irish Fiscal Policy Research Centre (publicpolicy.ie).

Luke Brosnan joined the ERSI in December 2023 as a research assistant in the Labour economics division. Luke holds a Bachelor’s degree in Applied Economics from University College Cork and a Master’s degree in Economic Research from the University of Cologne. His Master’s Thesis explored the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on student outcomes in the United States.

Prior to joining the ESRI, Luke worked as an applied microeconomics research assistant at the University of Cologne.